|

|

|

January 4, 2024 Spirit and Secularity: Why Can’t We Be Friends? The heights which, through the most gracious favor of God, mortal man can attain, in this Day, are as yet unrevealed to his sight….The day, however, is approaching when the potentialities of so great a favor will, by virtue of His behest, be manifested unto men…. All men have been created to carry forward an ever-advancing civilization….Those virtues that befit his dignity are forbearance, mercy, compassion and loving-kindness towards all the peoples and kindreds of the earth. — Gleanings from the

Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, CIX —

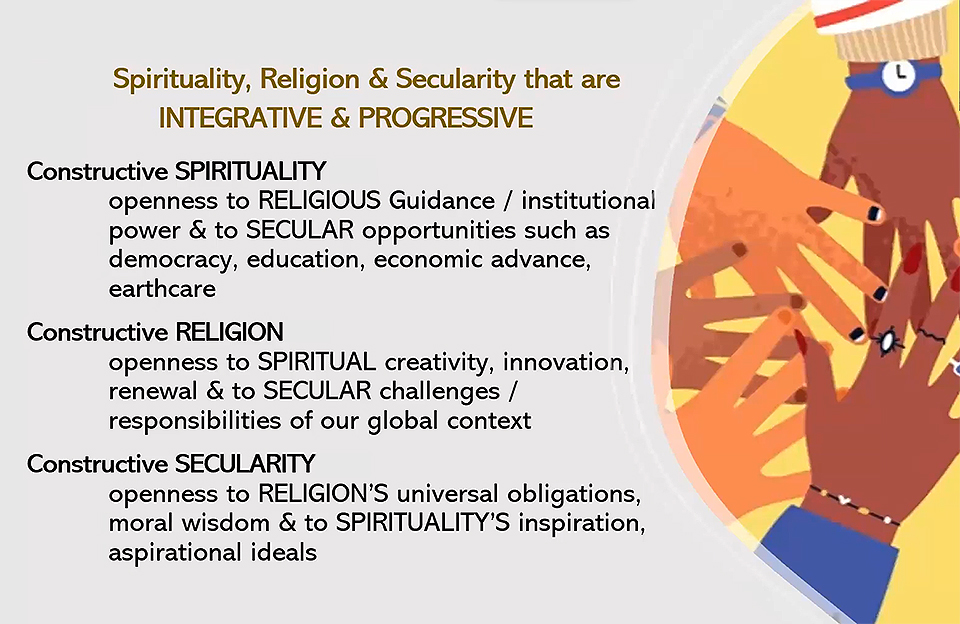

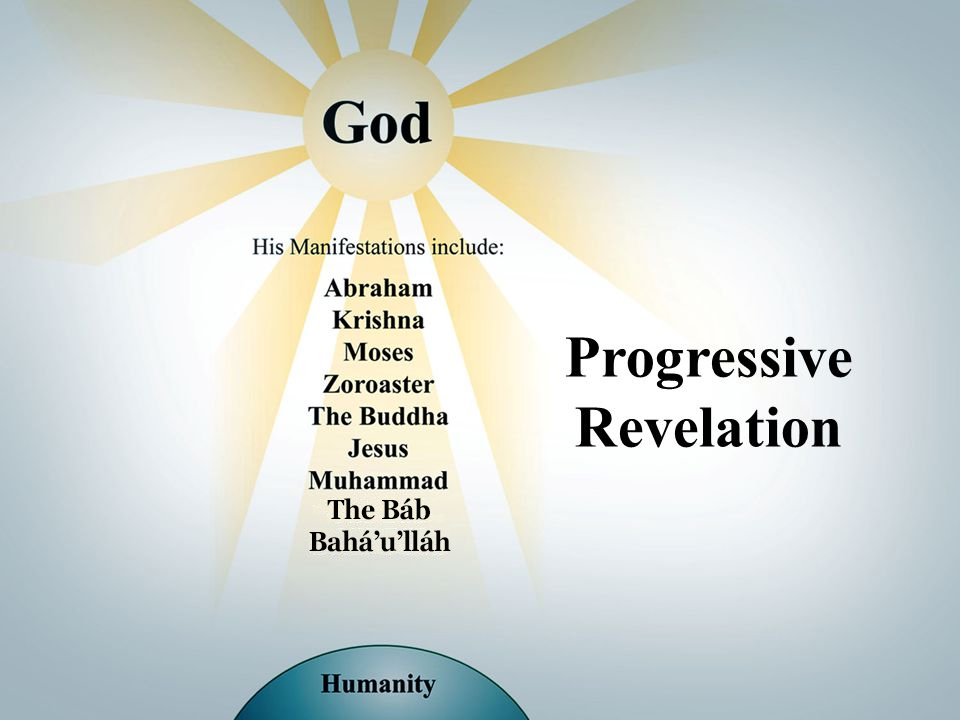

Harold Rosen sees the world differently. Long a Unitarian minister, now an interfaith educator and Bahá’í for over 20 years, Mr. Rosen gave a well-organized tour of an immense subject in an online talk in the “Big Ideas” series. He sought to untangle and resolve a false trichotomy: the prevailing belief that formal religion, spirituality and the workaday secular world are exclusive and mutually antagonistic worldviews. Rosen’s thesis was clear and profound: “We need all three!” Put simply, the religious perspective is based on a relationship with the Divine world and expresses how devotion to a great religious Founder ends in community. Our common “spiritual-but-not-religious” stance focuses on lofty purposes, seeking meaning and harmony via an expanded consciousness. Secularity as a worldview addresses human progress through the needs of daily living: work, education, health and family. Naturally, each worldview has some overlap with the other two, but are usually considered in isolation. (Rosen distinguishes “secularity” from the ideological “secularism” that rejects religion and spirituality entirely.) When one worldview rigidly excludes the other two, it falls into various forms of dogmatism. But Rosen argues that the intersection of religion and spirituality urges renewal of tradition and moral progress; the meeting of spirituality and secularity envisions conscious social evolution and higher human possibilities; and the conjunction of secularity and religion focuses on good works toward justice and peace. One step farther is found in the realm of the “unifiers”, where we draw from the best of all three perspectives in order to integrate, cooperate and build together. This, of course, is where the Bahá’ís and their friends try to locate themselves. “The distinction among the religious, spiritual and secular worldviews is roughly 500 years old,” Rosen explained. “Before the year 1500 C.E., we rarely pried them apart for examination.” Before then, personal and group perspectives tended to be more holistic. As we have advanced from ethics based on survival (constant danger, scarcity and anarchy) to ones founded upon identity (seeking advantage for one’s own tribe over others), we are now learning how to apply a “unity-based” worldview: recognition of one human family, pursuing shared progress while valuing the diversity of all. For Rosen, the “unifying” place where religion, secularity and spirituality meet is another way of expressing this worldview of what he calls “at-homeness in the world”.  How did we get here? He briefly explained two historical currents: one, the theory of progressive religious revelation in which Bahá’u’lláh presents himself not as the founder of yet another religion, but as the most recent agent of renewal in an eternal process of guidance and stimulation from the Divine; second, an account of the last 500 years in which changes, from the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution, served to undermine established beliefs, making a science-based secularity an increasingly attractive way of seeing the world and its workings. For Rosen, the rise of a balanced secularity – which he defines as an elevated form of citizenship – should be understood and welcomed. “High-minded citizenship is integral to religious and spiritual life; good citizens embrace ethical concerns for the common good, requiring constructive participation in secular domains.” As Bahá’u’lláh famously advised his followers, Every age hath its own problem, and every soul its particular aspiration. The remedy the world needeth in its present-day afflictions can never be the same as that which a subsequent age may require. Be anxiously concerned with the needs of the age ye live in and centre your deliberations on its exigencies and requirements. Bahá’u’lláh explained how contending religions, peoples and worldviews could be reconciled: that truth could be found among all great systems of thought; that we must be humble in the face of the Great Unknown; and, that each person has the capacity to discern some portion of the truth. For nearly two centuries now, the Bahá’í community has fervently worked to realize the vision of Bahá’u’lláh and has developed a global framework for action that allows anyone to join with it in its grassroots community-building. When religion, spirituality and secularity – which create only “stagnation, conflict, digression and despair” when isolated from another – are integrated, they become mutually reinforcing, constructive, and productive of “breakthrough, cooperation, progress and hope”. As an educator and “diplomat” seeking harmony among contending groups, Harold Rosen invites us to the place where the most humane and constructive aspects of secularity, spirituality and religion meet and reinforce each other, where the “unifiers” do the work that most needs doing. Big Ideas Video Archives, watch this and other previous presentations here: Video Archives |

|

|